Lebanon‘s economic meltdown has left the country “on the brink”, with one of its top doctors warning that medical supplies in hospitals across the nation have now reached critical levels.

The combination of coronavirus on top of an unprecedented economic crisis has created the “perfect storm”, Firass Abiad, the CEO of the Rafic Hariri University Hospital in Beirut, told Sky News.

“I think that, as they say, it never rains, it pours – and what we’re seeing is crises after crises,” Dr Abiad said.

“Each day you’re running from a power shortage to a medication shortage and so on. We’re trying to limit the affects of the shortages to non-essential, but the question is how long can we keep doing this?”

As manager of the country’s only designated hospital for COVID-19 patients, he finds himself at the heart of one aspect of a nation at breaking point.

“We are so much on the brink… All the services we are providing are in danger,” he said, adding: “At the moment, this call for [global] help is extremely important before we start cutting down on these life-saving services.”

His team gave Sky News a tour of the hospital – the biggest public hospital in the country. From department to department, they showed us a place struggling with multiple challenges.

There is a spike in coronavirus cases on top of an increase in regular patients who are no longer able to afford private healthcare.

The electricity is intermittent and the drug supply is dwindling – the consequence of eye-watering inflation. Ninety-five percent of medical supplies are imported and are now unaffordable.

There are financial crises now all over the world, with jobs gone and livelihoods lost. But here in Lebanon, it is on a different level.

In the hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit, 12 babies are in incubators. The in-house generators kept them alive when the state power was cut last week, but the generator fuel cannot be taken for granted.

Among the children is Chirine. She was born two weeks ago with brittle bones.

She looks desperate and is only alive thanks to nurses and doctors working endless hours on wages that are worth a fraction of what they once were, and with medicine that’s now at critical levels.

“It is really stressful, but again I am trying to just live day by day because there is no light at the end of the tunnel… I am just living now,” head of paediatrics Dr Nada Sbeiti says.

“Let’s finish July and see what August will bring to us.”

She adds: “We are really walking in a tunnel and we don’t know what’s coming. We hope there will be some light. We don’t know.”

North of the hospital, in the Nabaa neighbourhood, families are on the move. They are not moving far; just a few streets in many cases.

Evictions from homes that are no longer affordable are happening every day.

On one backstreet we find Elias. Pushing his family’s belongings in a shopping trolley, he is a snapshot of a broken country.

The husband and father-of-six was forced out of his rented home because he could no longer afford the month’s rent.

It was 400,000 Lebanese lira – not much more than £40 in the current economic crisis.

“I don’t have money, there is no work” he said, showing us around the new home – it’s one room, plus a cupboard-sized area, with a sink, a microwave and a toilet.

“There is no water, there is no electricity, there is no freezer and there is no fridge. But there is no electricity [in the neighbourhood], so even if you have a freezer and fridge, there is no electricity.

“It’s a blessing we still have a roof over our heads.”

“It’s very difficult, but now we’re going to a centre run by nuns, they prepare or distribute food,” his wife Salwa says.

“We eat whatever’s available. What can we say? Thank God.”

And school for the children?

“Since Christmas, I haven’t sent them [to school],” Salwa says, adding: “They stay at home with me, yes.”

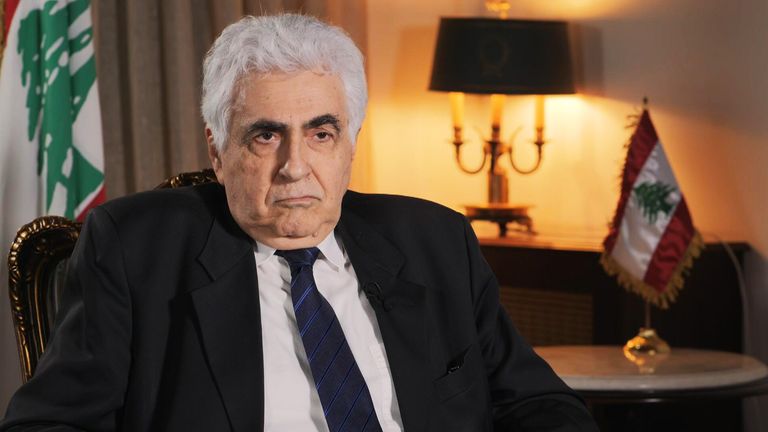

Lebanon’s economy minister Raoul Nehme, who many see as part of the political elite which helped cause this crisis, has warned that 60% of the population could be below the poverty line by the end of the year.

The country faces a severe import crisis of basic commodities like wheat, fuel and medicine because of a shortage of dollars. Food prices have soared by at least 56% since September, according to the World Food Programme.

The minimum monthly wage is now worth the equivalent of about £80 and savings in banks have lost much of their value.

Lebanon defaulted on its overwhelming foreign debts in March, and talks with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) collapsed last week. Bickering between cabinet, parliament, and the country’s central bank continues.

Beirut’s central square was packed with hope last October. I was there as hundreds of thousands put aside the sectarian divides which have plagued the country for generations.

Under one Lebanese flag they called for wholesale political change and an end to cronyism and corruption.

But the self-proclaimed people’s revolution came to nothing. And then coronavirus followed, paralysing the country.

In the now empty square I met Sami Zoughaib, an economist – but citizen, too – just trying to make ends meet.

He says: “All the money has been spent. And now you have a lot of losses. So the state owes a lot of money to the banks and they cannot repay them.

“And the amount of losses estimated by the government and the IMF is around $100bn (£79bn), and this in a country like Lebanon that is expected to have a GDP of $33bn (£26bn) this year.

“It’s three times the size of the economy and this is quite gargantuan. I personally don’t think there has been something of this size in the history of modern economies.”

The poor and the vulnerable are impacted the hardest, of course.

But across the board here, people are finding the lives they had – and the futures they thought they had – have simply disappeared: their savings have gone.

There are just two hours of state electricity a day here now. Even the traffic lights are out.

The politicians who caused this are now pleading for an international bailout. Without it, the collapse of a nation is close.