Talk of tax increases is in the air.

Government borrowing has ballooned as ministers have sought to insulate the economy from COVID-19.

The Office for Budget Responsibility, the independent fiscal watchdog that analyses the UK’s public finances, forecast this week that the government’s budget deficit this year will reach £372bn.

It warned that in order to reduce the national debt to 75% of GDP – the level the government was targeting prior to the pandemic – there would need to be both tax increases and cuts to public spending to restore the public finances to a sustainable level.

These measures would need to be around £60bn per decade.

So where will the money come from?

One saving that seems increasingly likely is the scrapping of the so-called “triple lock” under which the basic state pension rises each year by a minimum of either 2.5%, the rate of inflation or average earnings growth, whichever is the greatest.

That would save £8bn a year, while even switching to a ‘double lock’, removing the 2.5% element, would save half that.

But unlike the aftermath of the financial crisis, when public spending cuts did most of the heavy lifting, it seems tax increases are more likely to be involved in this latest attempt to repair the public finances.

So which taxes might go up?

Four taxes – income tax, VAT, national insurance and corporation tax – are the main revenue raisers for the government.

During the March budget unveiled by Chancellor Rishi Sunak, the four were together expected to account for two-thirds of taxes raised by the government during the 2020-21 financial year.

The next most important, excise duties, council tax and business rates, raise comparatively little.

The three combined were this year expected to raise just over half the amount raked in via income tax.

Raising any of the four could be difficult.

To take them in turn: the government in March scrapped plans to cut corporation tax, so raising it further might be tempting.

Putting up the rate of corporation tax from 19% to 20% would, ordinarily, rake in an extra £2.5bn.

These, though, are not ordinary circumstances and, with company profits set to collapse this year, hiking corporation tax would make no meaningful difference.

Meanwhile, although Treasury polling has indicated the public would be receptive to a rise in corporation tax – it’s funny how the public always welcomes tax increases when levied on others – there will be pressure in coming years to cut corporation tax, not least to demonstrate the UK’s attractiveness to business following Brexit.

:: Listen to The World Tomorrow on Apple podcasts, Spotify, Google podcasts and Spreaker

National insurance, the next most important tax, is likely to go up for some earners.

The chancellor hinted, when outlining the generous support he was gave the self-employed at the height of the crisis, that they could expect to pay national insurance at the same rate as people on PAYE in future.

This was something Mr Sunak’s predecessor-but-one, Philip Hammond, tried to do before being slapped down by Theresa May.

His logic, though, was impeccable – now that the self-employed receive the same basic state pension as employees, there is no reason for them not to be paying national insurance contributions at the same rate.

Similarly, the earnings of someone of state pension age do not currently attract national insurance, something Mr Sunak may seek to change.

There is no logical reason why £1 earned by a 67-year old should be taxed less heavily than £1 earned by a 60-year old on the same wages.

Such a move would bring in £1bn annually.

Raising VAT would be harder.

It might be possible some years from now but, as the chancellor has only just cut VAT for the hospitality sector, putting it back up again would not benefit consumer spending in the near term.

More effective, in terms of raising money, would be to widen the scope of VAT and include items currently zero-rated, including water bills, prescription drugs, books, children’s clothes and food.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) calculates the government loses £48bn annually from zero-rating – although such a move would be politically explosive.

As for income tax, any increases would need to be wide-ranging, rather than targeted at higher earners.

This is a group that is very sensitive to higher rates of income tax.

The last big increase, when then-chancellor Alistair Darling introduced a new 50% tax rate in the dying days of Gordon Brown’s government, actually proved counter-productive.

But the tax raked in from the new band rose by £8bn when, in 2012, former chancellor George Osborne cut the 50% additional rate to 45%.

Moreover, even if the 40p and 45p tax rates were increased, it would not bring in meaningful sums because there are not enough high earners in the economy.

The IFS points out that, in 2017-18, more than a quarter of all income tax was paid by just 300,000 individuals earning more than £150,000 a year and almost half of all income tax revenues that year came from just 3% of all taxpayers.

This can also be shown by HMRC estimates on how much would be raised by increasing individual tax bands.

Raising the additional rate of income tax from 45% to 46% would bring in just £200m extra and raising the higher rate from 40% to 41% just £1.2bn.

But putting up the basic rate from 20% to 21% would raise £4.6bn.

So, to bring in a sum of money capable of moving the dial, an income tax increase would have to be levied on all earners.

This shortage of genuinely wealthy people also explains why a wealth tax, proposed by some, would also be problematic.

A wealth tax would not raise meaningful sums of money unless it were levied on homes and pensions – which would be politically explosive.

Even a narrowly-defined wealth tax would be hard to bring in.

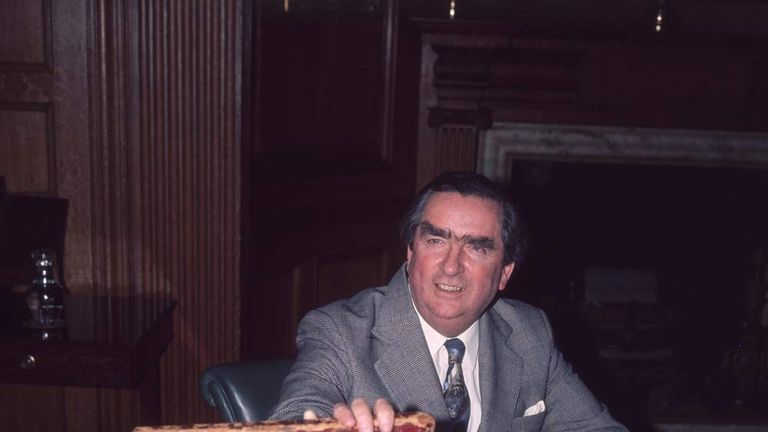

Denis Healey, Labour chancellor from 1974-1979, famously promised to “squeeze the rich until the pips squeak” when he came to office.

He subsequently reflected in his memoirs: “In five years I found it impossible to draft [a wealth tax] which would yield enough revenue to be worth the administrative cost and political hassle.”

So raising taxes is harder than it looks, which is why Mr Sunak has commissioned a review of capital gains tax, (CGT) even if he was at pains to stress to MPs today that this did not mean increases in CGT were coming.

Yet there is certainly a case for reforming CGT.

Under both Mr Brown and Mr Osborne, it has become hideously complex, enabling some people to disguise income as capital gains.

One way around this would be to equalise rates of CGT and income tax, something former chancellor Nigel Lawson did with great success in 1988, which would bring in more money.

The biggest single money-raiser, as regards CGT, would be to levy it on the sales of primary residences, a measure that could raise more than £20bn, but which is a non-starter politically.

But it does feel as if change may be coming for this tax.

It is all a long way away from when former Prime Minister John Major told the 1991 Conservative Party conference that his long-term ambition was to abolish capital gains and inheritance taxes with “wealth cascading down the generations”.