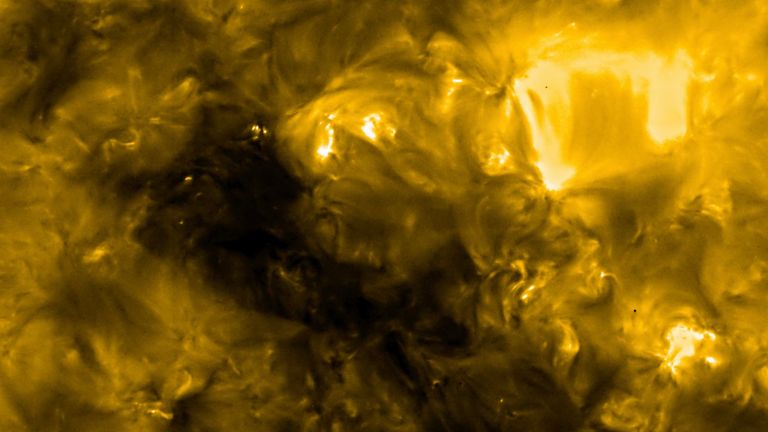

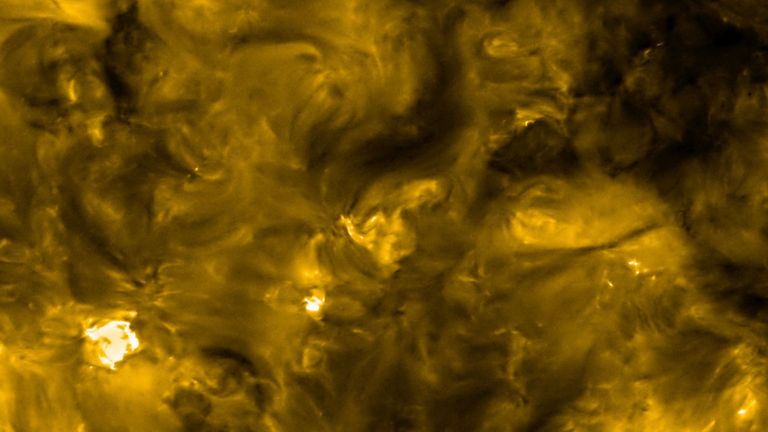

The closest images ever taken of the sun have been revealed, showing mini solar flares dotted across its surface.

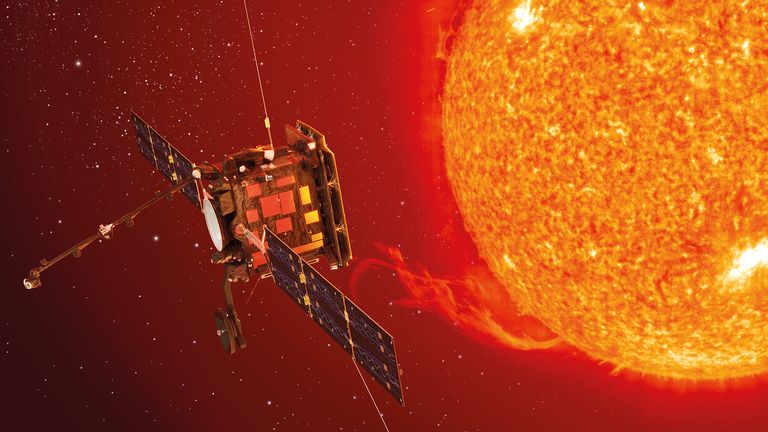

The Solar Orbiter, a European Space Agency satellite designed and built in the UK, took the pictures when it came within 47 million miles of the sun’s surface in mid-June.

Known as a perihelion, the close pass put the spacecraft between the orbits of Venus and Mercury.

Solar flares were seen on the surface, which are brief eruptions of high-energy radiation from the sun’s surface that can cause radio and magnetic disturbances on the Earth.

Dr Caroline Harper, head of space science at the UK space agency, said the scientists were excited by the presence of “campfires” that are “millions of times smaller than the solar flares”.

She said: “We do not really know what they [the campfires] are doing but there is speculation that they might play a role in coronal heating, a mysterious process whereby the outer layer of the sun, known as the corona, is much hotter [around 300 times] than the layers below.

“These campfires may be contributing to that in a way we do not know yet.”

Scientists will now monitor the campfires’ temperatures using an instrument on the spacecraft known as Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment, or SPICE.

The Solar Orbiter will also help scientists piece together the sun’s atmospheric layers and analyse the solar wind – the stream of highly energetic particles emitted by the star.

This could help scientists make predictions on space weather events which can damage orbiting satellites and disrupt infrastructure on earth that mobile phones, transport, GPS signals and electricity networks rely on.

Dr Harper added: “The science will allow us to start improving our operational capability to predict the space weather, just like you predict the weather here on Earth.”

The satellite will go close to the sun every five months, and at its closest will only be 26 million miles away, closer than Mercury, the planet nearest to the sun.

It will use the gravitational force of Venus and Earth to adjust its trajectory, before getting into operational orbit in November 2021.

“At that point, it will send back much more data about the sun’s surface,” Dr Harper said.

“It will also be flying over the poles of the sun and take images.”

She added that the UK has leading roles on four of the 10 scientific instruments on board the Solar Orbiter, which was constructed by Airbus in Stevenage and blasted off from NASA’s Cape Canaveral site in Florida on 10 February.