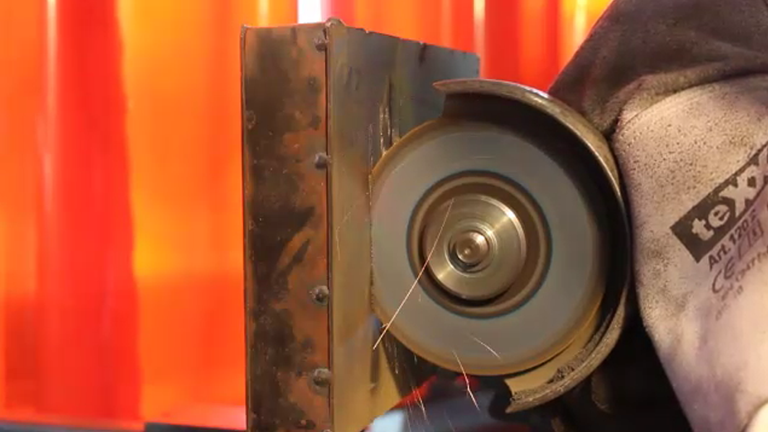

Researchers have developed an “uncuttable” material capable of deflecting grinders and cutting tools in what is thought to be a world first.

The material, known as Proteus, is six times lighter than steel due to its porous make-up.

One of the people behind the invention, Dr Stefan Szyniszewski from Durham University, told Sky News that materials such as grapefruits and molluscs inspired the creation – believed to be the first manufactured uncuttable material.

“The grapefruit is actually very resistant to free-fall,” he explained.

“So you can drop it from a couple of metres and it will still remain intact – because the peel of grapefruit is made of porous sponge, a sponge within a sponge within a sponge, and this makes the skin very light.”

Dr Szyniszewski said the mollusc shell was the “more important” of the inspirations, adding: “The seashell is very resistant to predators, so it doesn’t open easily when the shark wants to eat it.

“It’s quite surprising, the resistance of the shell is about 2,000 higher than the bricks it is made of.

“This is because when you try to cut it open, the crack has travelled via this maze of this soft material in between the hard brick and this takes a lot of energy.”

Dr Szyniszewski, part of a team of researchers from England and Germany who created Proteus, added: “What I’m really excited about is that it’s just a concept, so we made it out of steel and ceramic spheres.”

:: Listen to the Daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

Dr Szyniszewski said the spheres can be swapped out for other materials, like plastic or foam, but still remain strong.

He puts Proteus’s “uncuttable” nature down to the way the ceramic spheres inside the steel act as “mini sandbags”, which will break into particles and resist fast moving objects, such as grinders and saws – even blunting them against their own force.

The material can also be easily manufactured, with Dr Szyniszewski saying it is akin to “baking a cake”.

Metallic powder is used, alongside a foaming agent and then the ceramic elements, before it is put into the oven to form the new material.

Researchers believe the findings can be applied primarily in the security and safety industries, allowing armoured vehicles to be lighter and stronger, or making locks that cannot be broken.