COVID-19 has had some very stark and very obvious consequences.

The US has less than five percent of the world’s population but almost a quarter of its coronavirus fatalities.

But there is also a hidden horror unfolding here and it may soon get even worse.

People with mental health and addiction issues, already vulnerable, have found themselves even more exposed.

Some have simply been unable to cope.

In May, there was a 48% rise in suspected overdoses in America compared to the previous year.

That’s according to data collected by the Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program. It is a staggering figure.

At St Vincent’s Hospital in Westchester, New York, a division of St Joseph’s Medical Centre, I saw the cruel reality of that first hand.

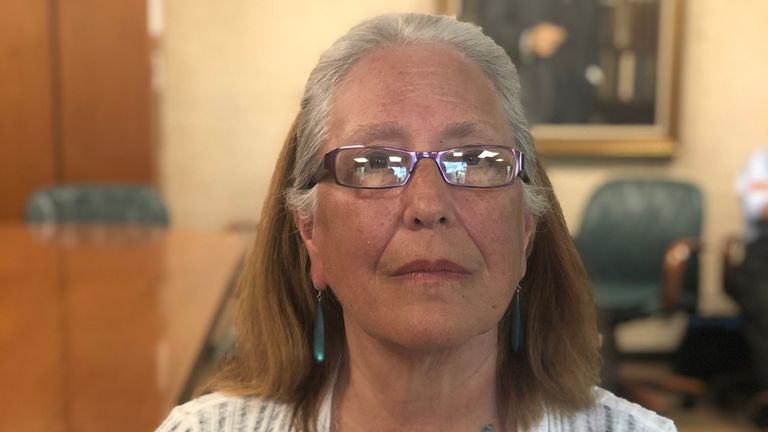

Jenny Stasikewich recently lost her son to an overdose – 28-year-old Eric Bender.

She told me he’d started to turn his life around, things were looking up after taking drugs for 10 years and she was – and is – incredibly proud of him for that.

“He’d been clean for a year,” she explained, and before COVID-19 he’d been attending the hospital for counselling and drug tests five days a week.

But as the pandemic took hold, he could no longer visit the counsellor he valued so much in person.

He self-isolated and his world was quickly turned upside down. The only way of communicating with his counsellor was on calls and he became less engaged.

As the weeks went by, he started to spiral.

“He had his birthday on 9 April and on 5 May he passed away from a drug overdose,” his mother told me with devastating starkness.

Jenny firmly believes Eric didn’t intend to die and that he would have been alive if it wasn’t for the pandemic.

He is, she says, “collateral damage” and she wants him to be counted as part of the official death toll of COVID-19.

Dr Christopher Aloezos, medical director at St Vincent’s Outpatient Addiction Programme, said: “Lots of our patients are experiencing grief and loss unexpectedly – loss of a job, family member and purpose and identity.

“We’ve seen more severe illness and a spike in it.”

Despite the difficulties posed by COVID-19, St Vincent’s was able to keep admitting in-patients and out-patients at the height of the pandemic.

It even started to absorb some of those who couldn’t attend other clinics. But the way they work changed significantly.

Group interaction is seen as a big part of helping people to recover. But that has not been possible during COVID-19.

They’ve had to rely on a lot of video calls.

Tony Shimkin, a peer counsellor and a recovering addict himself, told me: “All of a sudden people who were used to reconnecting with peers and socialising were forced into isolation and that was the hardest part… so many people got sad, depressed and their best friend all of a sudden was their drug of choice.

“We saw a lot of people returning to use and relapsing.”

Tony himself lost three people he knew in just one week.

:: Listen to Divided States on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

When people have stopped taking drugs, they are especially vulnerable as their tolerance level is reduced.

Tragically that has meant some people who had been doing well before the pandemic faced a huge battle.

St Vincent’s wants people to come to them. Their doors are open and they’re finding new innovative ways to help save lives. They are a beacon of hope in what has been a deep sea of despair for so many.

It is humbling and impressive to see how they’ve worked around such a terrible time. Their staff are dedicated and innovative.

But they know too that there will be months, possibly years, of struggle and challenge ahead.