Hundreds of thousands of people with mental health problems, including children as young as ten, are forcibly chained up in cages and kept in appalling conditions without medical help.

The practice known as ‘shackling’ is commonplace in 60 countries across the world, and sees adults and children as young as 10 restrained or locked up for days, weeks and even years at a time, charity Human Rights Watch has found.

The majority are kept against their will in cramped, unsanitary conditions either in government-run institutions or at home by their families because of stigma and a lack of mental health services.

“Shackling people with mental health conditions is a widespread brutal practice that is an open secret in many communities,” said Kriti Sharma, senior disability rights researcher at Human Rights Watch.

“People can spend years chained to a tree, locked in a cage or sheep shed because families struggle to cope, and governments fail to provide adequate mental health services.”

An investigation by the charity spanning 16 countries found victims in Asia, Africa and South America are often subjected to cruel, untested treatments by healers and face physical, sexual and emotional abuse.

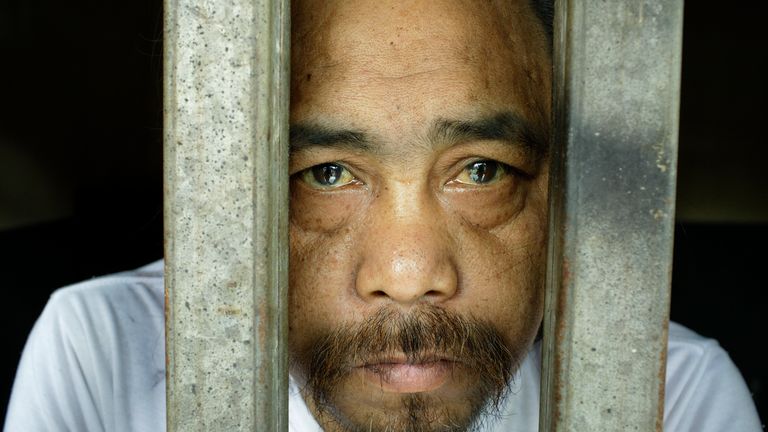

Made, a man with a psychosocial disability was locked in a purpose-built cell on his father’s land for two years in Bali, Indonesia.

He said: “I feel sad, locked in this cell. I want to look around outside, go to work, plant rice in the paddy fields. Please open the door. Please open the door. Don’t put a lock on it.”

Healers and family members typically practice shackling as a punishment due to the belief mental health conditions are the result of evil spirits or having sinned.

Others feel they have no other option thanks to the high cost of medical treatments and the distance to hospitals.

Shackling is considered the only option for some families who are afraid their relative might hurt someone or themselves, the charity said.

Paul, who suffers with a psychosocial disability, has been chained in a faith healing institution in Kisumu Kenya for five years.

He said: “The chain is so heavy. It doesn’t feel right; it makes me sad.

“I stay in a small room with seven men. I’m not allowed to wear clothes, only underwear.

“I have to go to the toilet in a bucket. I eat porridge in the morning and if I’m lucky, I find bread at night, but not every night.

“It’s not how a human being is supposed to be. A human being should be free.”

People on the ground in 16 countries for Human Rights Watch found shackled people of all ages living in extremely degrading conditions.

They have evidence the practice is happening in up to 60 countries.

In 2018 and 2019 Human Rights Watch visited 28 state-run and private facilities in Nigeria where they found the youngest patient was a 10-year-old boy and the oldest person was an 86-year-old man.

Meanwhile, it’s thought that in China, about 100,000 people are shackled or locked in cages in Hebei province alone, near Beijing.

In Indonesia, 57,000 people with mental health conditions have been in shackles at least once in their lives and in India thousands were found chained in the state of Uttar Pradesh.

In Morocco, the government released over 700 people chained in one shrine alone, about 50 kilometres from Marrakesh in the country’s southwest.

Unhygienic conditions in state-run institutions, where it is not uncommon to see multiple people chained together, are a concern for charities, particularly considering the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mr Sharma said: “In many of these institutions, the level of personal hygiene is atrocious because people are not allowed to bathe or change their clothes and live in a two-metre radius. Dignity is denied.”

Additionally, shackling poses serious physical and mental health risks.

Research has found it can cause post-traumatic stress, malnutrition, infections, nerve damage, muscular atrophy, and cardio-vascular problems.

A lack of resources or standardised care in many countries has been blamed for the shocking conditions many mentally ill or disabled people are left in.

Despite shackling being widespread across the globe, experts said the problem remains “largely invisible” as it often occurs behind closed doors and is hidden by families who fear the stigma of having a mentally unwell relative.

There is no global data to show the exact scale of the problem and no international response to help tackle the issue.

“It’s horrifying that hundreds of thousands of people around the world are living in chains, isolated, abused, and alone,” Mr Sharma said.

“Governments should stop brushing this problem under the rug and take real action now.”

As a result, Human Rights Watch have launched a global #BreakTheChains campaign to end shackling of people with mental health conditions, ahead of World Mental Health Day on October 10.

The charity is calling on national governments to ban the practice, reduce stigma, and develop quality, accessible, and affordable community mental health services, and monitoring of state-run and private institutions to improve standards.