Steam is vented through exhaust stacks at Great River Energy’s Coal Creek Station in North Dakota. Some of the largest banks in the U.S. have cut back on lending to the coal sector in recent years, but they need to do much more to lower the climate risk in their loan portfolios, a new report argues.

Daniel Acker | Bloomberg | Getty Images

The financial world is beginning to reckon with a hard truth: Climate change poses a clear threat to the entire U.S. financial system.

With wildfires tearing through the West Coast, hurricanes pummeling the South, and a megadrought emerging in the West, investors, lawmakers, former regulators, and advocates are setting off alarm bells for U.S. financial regulators and the banks they regulate about the danger our markets face if they do not act to protect against that risk.

This summer, some of the country’s largest investors sent public letters to the heads of financial regulatory agencies, asking them to take up the mantle on climate change as a systemic financial risk. California Controller Betty Yee penned an op-ed urging for “leadership from every U.S. financial regulator to transition to a resilient, sustainable, low-carbon economy and avoid a climate-fueled financial collapse.”

Senate and House Democrats released reports detailing the risks and calling for stronger measures to mitigate them. In September, a subcommittee of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission even issued its own report, advising its own agency and many others to step up and lead on climate to avert a potential crisis.

Now, a new look under the hood at U.S. banks puts the extent of that risk in stark relief.

The U.S. banking sector is far more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change than banks are letting on, according to new research. That vulnerability should concern not only major investors and regulators, but every person with savings in a bank or money invested in a retirement fund.

This research finds that, in addition to losses from the physical impacts of climate change, every major U.S. bank faces the potential for dramatic losses from the failure of the companies they loan to plan for a transition away from fossil fuels. These findings come from an assessment not only of U.S. banks’ fossil fuel lending, but of their broader loan portfolios — including the risks that an unplanned-for-transition away from fossil fuels would have on the assets in the sectors that rely on those industries most, such as agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation.

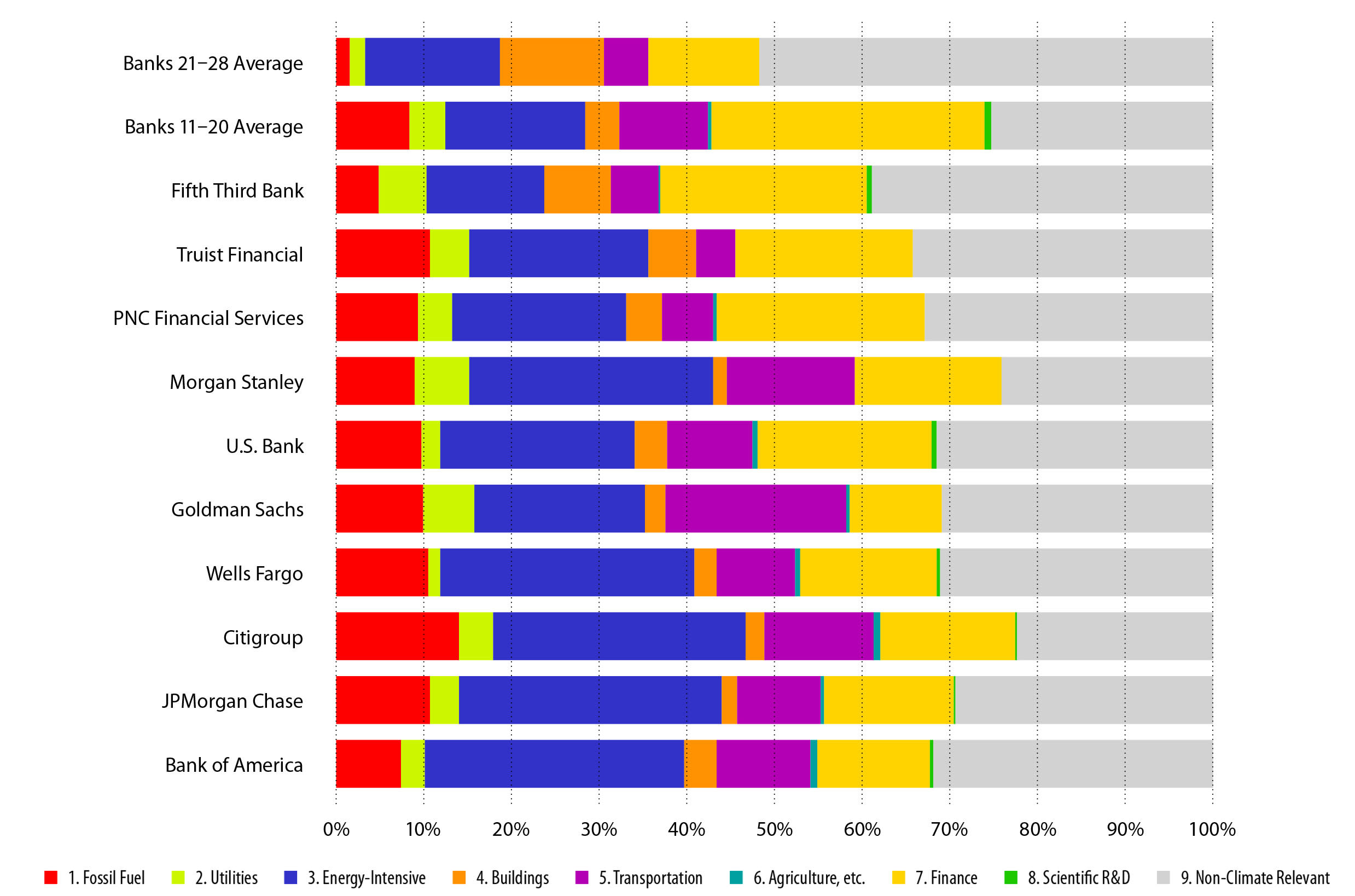

In its new report, Financing a Net-Zero Economy: Measuring and Addressing Climate Risk for Banks, Ceres finds a significant level of exposure to climate risk within the largest banks’ syndicated loan portfolios.

Ceres

When considering this more complete view of climate risk, this exposure is so significant that it could trigger a financial crisis, with more than half the syndicated lending of all major U.S. banks being exposed to significant climate risk, which could translate into more than $100 billion in losses. What’s more, that figure only reflects a portion of their balance sheet, and assesses only one type of climate risk. If the full balance sheet were publicly available, the potential losses would likely be even greater.

So what’s a bank, or a regulator, to do?

U.S. regulators can do what capital markets leaders are urging them to do — regulate climate change as a systemic financial risk. This includes mandating climate risk disclosure from the sectors they supervise, and requiring that financial institutions incorporate climate risk into their scenarios analysis and into their stress tests. Central banks in Europe, Canada, Japan, and New Zealand are already doing this. It’s time U.S. regulators do the same.

We are beginning to see U.S. regulators begin to act. California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara created a public database of green insurance products, New York Department of Financial Services Superintendent Linda Lacewell told insurance companies they must incorporate climate risk into their scenario analysis. Regional Fed offices, particularly those in San Francisco, Richmond, and New York, are taking steps to better understand the systemic risk of climate change.

This movement is bound to grow as climate change worsens and the financial implications of not acting become more clear.

But banks can’t just wait for the coming regulation. They need to proactively assess and disclose their full exposure to climate risk, which will benefit them regardless of new legislation or regulation. The current focus is on banks’ syndicated loans because that’s what’s publicly available. In order for banks, their investors, their customers, and their regulators to more thoroughly understand the sector’s vulnerability to climate change, the banks must quantify climate risk at both the firm and portfolio levels across all asset classes and business lines.

Banks that are already measuring their vulnerability to climate change should dive in deeper, and start leveraging their lending power to make sure those they loan to disclose their emissions, and lay out their plans for business in a carbon-constrained world. We’ve begun to see this with banks moving away from coal financing. We need to see them conduct this kind of engagement across their lending portfolios. If that engagement doesn’t lead to action, they should be ready to walk away.

Lastly, banks should act to mitigate their exposure to climate risk through direct client engagement and by committing to align their client portfolios with the goals of the Paris Agreement. These commitments should include detailed interim targets and specific timelines for sectoral portfolios to reach net-zero emissions by or before 2050. We’ve seen encouraging progress recently in the form of commitments from major U.S. banks like Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase. More work remains to be done, however, by these firms and others to get to the level of specificity and ambition needed.

Banks, and regulators have their work cut out for them, as do the investors and customers that rely on them, but the work will be far harder and more expensive the longer they wait. Banks’ vulnerability to climate change will continue to mount regardless of the outcome of the U.S. presidential election. To avoid another systemic-scale crisis like the world experienced in 2008-2009, only concerted, systemic, preventative action will do.

—By Steven M. Rothstein, managing director of the Ceres Accelerator for Sustainable Capital Markets, and Dan Saccardi, senior director, company network, at Ceres. Ceres recently released the report Financing a Net-Zero Economy: Measuring and Addressing Climate Risk for Banks.