Could it be that two years of agony for Boeing are finally over?

The aerospace giant – America’s biggest exporter – has been in a state of turmoil since being forced to ground the 737 MAX after crashes in Ethiopia and Indonesia in 2018 and 2019 killed 346 people.

The longest grounding in commercial aviation history, 617 days in total, has cost Boeing at least $20bn (£15bn) and forced the company to cut tens of thousands of jobs, some 19,000 of them in this year alone, with at least another 7,000 to come.

That does not include the countless redundancies at Boeing’s suppliers which began when the company froze production of the 737 MAX in December last year.

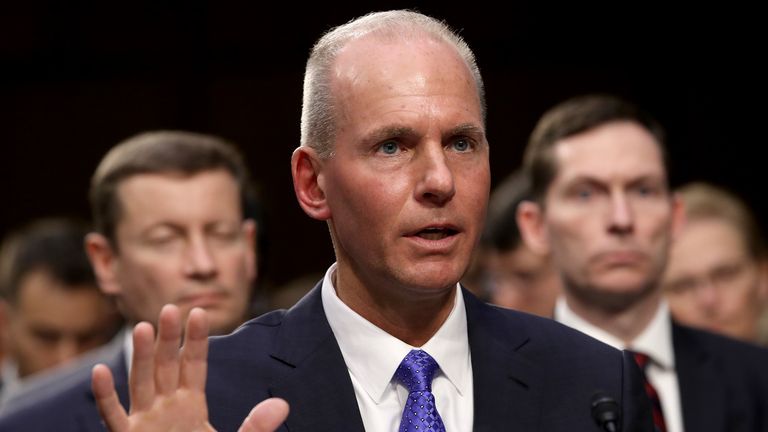

Among those losing their job was Dennis Muilenberg, the former chief executive, whose abject failure to apologise to families for the crashes in a timely manner was a textbook example of “how not to do it” which will be taught for years to come in business schools.

Now, though, the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the main regulator, has cleared the way for Boeing’s best-selling passenger jet to resume commercial flights.

The decision raises a number of questions.

The first is how quickly Boeing can clear the regulatory hurdles the FAA and others have set before the plane can actually return to the skies.

The FAA has demanded more training for pilots and software updates to prevent a repetition of the incidents that led to the crashes.

That may take time, at least until the end of next month, when American Airlines has pledged to use the aircraft on its Miami to New York route two days before New Year’s Eve.

Southwest Airlines, another of the big four US carriers, has said it hopes to have the planes in the air by the middle of next year.

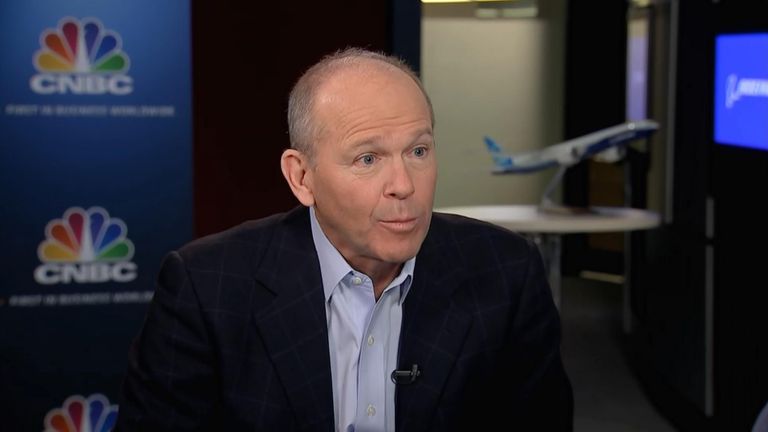

Steve Dickson, the FAA administrator, told CNBC today: “It’s the most scrutinised airplane in history and it’s ready to go.

“This is not a typical certification process we have undergone.

“But this is not the end of the safety journey – there is a lot of work for Boeing and the airlines to do.

“This airplane, the work that we’ve done with the design changes and the training changes, [means] those kind of accidents can no longer happen.

“The training is straightforward. I did it.”

Mr Dickson brushed off a recent leak of emails that suggested some Boeing employees were dismissive of the FAA.

He added: “We have reset the relationship with Boeing.

“Our work has been validated by a supervisory board and this is something we will incorporate into our future certification work on other aircraft.

“The relationship with the Boeing leadership is very professional.”

Other regulators, most notably the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) but also others in countries like China and Brazil, will have to give certification of their own.

EASA has already indicated it is satisfied with the progress that Boeing has made but other regulators may require more convincing.

Mr Dickson said the FAA had worked closely with its counterparts elsewhere and would be sharing information with them related to its decision to unground the aircraft.

The second question concerns how quickly Boeing can resume deliveries of the 737 MAX to those customers who have ordered them.

It has an estimated 4,100 of the aircraft on order.

An estimated 450 aircraft that have already been built are sitting in various storage locations across the US but, due to the collapse in air travel, there is little rush on the part of airlines to collect them.

One of the biggest orders is from Ryanair, which has a firm order for 135 of the aircraft, plus options over a further 75.

Michael O’Leary, Ryanair’s chief executive, said earlier this month that the airline was waiting for Boeing to “finalise a reasonably credible delivery schedule to us”.

Other carriers that still have outstanding orders include the tour operator TUI, the Polish carrier Enter Air and SIA, the parent of Singapore Airlines.

Lion Air, the Indonesian carrier involved in one of the two fatal crashes, also has more than 200 of the aircraft on order.

However, hundreds more orders for the aircraft have been cancelled, including ones from the Romanian carrier Blue Air and from the Hong Kong-based aircraft lessor BOC Aviation.

Norwegian, which is fighting for its life after being refused more financial support from its government, has cancelled its entire order of 110 jets.

In the meantime, Boeing has been trying to find buyers for the scores of jets completed for those customers who have since cancelled orders.

Among those on whom it is understood to have focused its efforts are Delta, the only one of the big four US carriers not to have ordered any of the 737 MAX to date, although the latter has resisted the temptation to do so for now.

Crucially, a number of airline executives have been forthright in insisting they still have confidence in the aircraft, most notably Willie Walsh, the former chief executive of International Airlines Group, the parent company of British Airways and Aer Lingus.

Mr Walsh, a former pilot who stepped down in September after 15 years in the job, stunned the industry when he announced an order for 200 of the aircraft at last year’s Paris Air Show.

He said at the time: “I have great confidence in Boeing and great confidence in the MAX. It will make a great addition to our fleet.

“I would not hesitate to get on board the MAX aircraft tomorrow. I believe the aircraft is safe and I believe what Boeing is doing is sensible.”

To that end, the support of Mr Walsh and a respected carrier like British Airways will go towards answering the third and arguably most critical question, which is whether the public will feel confident in getting on board a 737 MAX in future.

The issue poses a dilemma both for Boeing and for the airlines themselves as they grapple with the issue of whether the 737 MAX brand name is irreparably damaged.

Some have called for Boeing to rebrand the aircraft, among them President Trump, who tweeted last year: “If I were Boeing, I would fix the Boeing 737 MAX, add some additional great features and rebrand the plane with a new name.”

Those sentiments have been echoed by a number of Boeing’s customers.

These include the leasing company Air Lease, which has 150 of the aircraft on order, and Kenya Airways.

A number of Boeing’s customers have even taken matters into their own hands, among them Ryanair, which last year replaced the wording 737 MAX on one of the aircraft with ‘737 8200’.

Mr Dickson said today: “I understand the concerns [about it taking to the skies again but] I would put my own family on it.

“I plan to fly on it myself – I believe it is a safe aircraft and I stand behind that.”

Today is a moment a vast relief for Boeing and its customers.

A year ago a lot of people were even speculating that the 737 MAX would never take to the skies again.

It was no surprise to see shares of Boeing, which since the start of the year have fallen by nearly 32%, rise by almost 8% at the open.

But the company still has immense challenges.

At the end of 2018, prior to the second fatal crash, Boeing’s debt stood at $13.8bn (£10.2bn).

Today, its debts stand at $63bn (£47bn), just at a time when its cash flow has dried up and when it is still under pressure to spend heavily to compete effectively with its bitter rival Airbus.

Boeing has just flown through one immense period of turbulence.

There may be just as challenging air pockets ahead.