Boris Johnson was probably right to kick off a much needed conversation about devolution of power last week, even if the manner of doing so – saying it had been a disaster in Scotland – was for many Tories the kind of quip the head-exploding emoji 🤯 was invented for.

In fairness to the PM, you need to highlight this subject in an eye-catching way because it is so immensely dull and complex.

Any question to which well-meaning people can then suggest the answer is a “constitutional convention” (Google it and you’ll wish you hadn’t) is often better not asked in the first place. Devolution in all its forms is a mess – precisely because it is just so boring and complex to sort out.

The coronavirus pandemic has driven home in Westminster what has been obvious in Manchester, Belfast, Edinburgh, Cardiff, Birmingham – most places outside of London in fact: That devolution of power is a serious business, and has involved the transfer of serious powers.

Every bit of local regional and national government has had to step up to the plate to deal with the effects of COVID-19, causing much wailing and gnashing of teeth in Downing Street.

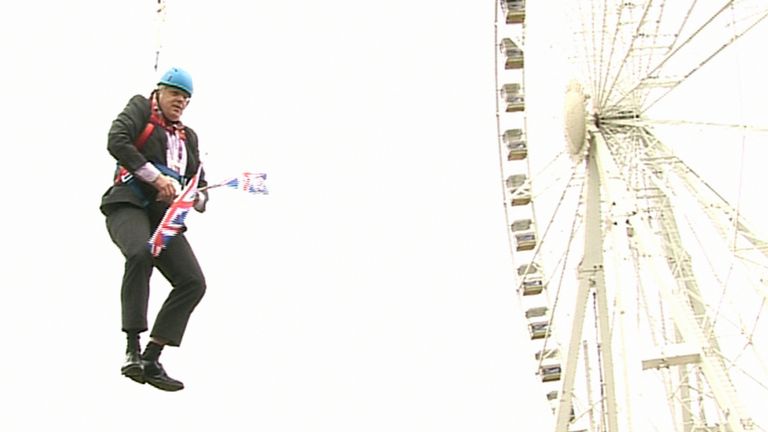

It is presumably no coincidence that London mayoralty has some of the weakest powers of any devolution deal. City Hall and its bully pulpit alone were the travellator which took Mr Johnson from backbench obscurity to Downing Street.

Westminster was, and is, vaguely in favour of the devolution of power, but cannot decide where and how decisions should be made, and ministers always have an aversion to anything that looks or smells like an alternative powerbase.

So it’s all inconsistent: the devolution settlement with Edinburgh is different to the one with Cardiff (the scale of tax-raising powers in the former being the biggest difference). Northern Ireland operates without directly elected government for years at a time.

Meanwhile in England each “City Deal” is different: NHS spending is devolved to the 10 councils in the Greater Manchester region, but not in Birmingham. Some areas are without mayors altogether, and after the PM’s row with Andy Burnham last month, they seem likely to stay that way.

The uncertain attitude to devolution was captured by Mr Johnson rather brilliantly in his speech to Tory Scottish conference.

“Devolution should be used not by politicians as a wall to sequester, to break away, an area of the UK from the rest,” Mr Johnson said.

“It should be used as a step to pass power to local communities and businesses to make their lives better. It’s that kind of localism which I believe in and want to take further.”

It’s entirely ambiguous who these “local communities” are – be they councils, regional authorities or mayors. He won’t tell us where power should be devolved to. Maybe he doesn’t know.

The Tory answer seems to be putting Union Jacks on everything. Labour’s answer looks like it will be a constitutional convention. Neither answer will go down well with those trying to run services across the country.

Nobody captured this ambiguity better than George Osborne, whose messy legacy Rishi Sunak must now decide whether to clear up. For some he is the champion of the Northern Powerhouse – he oversaw the “City Deals” and was in office when more powers were handed to Scotland.

Yet he was also the Chancellor who put an extraordinary squeeze on council day-to-day spending. A breakdown by the Financial Times of council spending between 2010 and 2015 revealed that local government budgets cut by £18bn in real terms.

This trend accelerated. The House of Commons library says this year’s local government finance settlement leaves most authorities “well below” the level of funding that they were receiving in 2015.

Mr Osborne raided local authority budgets with impunity because he knew there was very unlikely to be political repercussions in Parliament, unlike squeezing the education and welfare budgets which both came to his cost.

This legacy, on top of present day problems, is unsettling leaders of Tory councils in Conservative heartlands.

Keith Mans, the Tory leader of Hampshire council, told me that he wished his party had been more concerned with local government. Now they want sums which sound eye-watering.

“We would expect with the annual funding round going on at the moment to expect at least the same increase as the health service is getting because our increase in demand is very similar,” Mr Mans said, adding: “The NHS has got £30bn more. Local government has got £20bn less.”

There are similar views from the Tory leader of Leicester Council Council, who said the government made a promise at the start of the pandemic it now looks in danger of breaking.

“When we first started off with the coronavirus – the government said whatever it takes, and I took that to mean that whatever we spent would be covered by grant,” said Nicholas Rushton.

“They have been relatively generous but they’ve possibly only funded 50% of our increased costs. The problems are entirely about money. We need money to carry on what we’re doing.”

He spelt out which services were at risk. “20% of our budget is spent on things that people appreciate that isn’t protected (in law so could be cut). Subsidising buses isn’t protected, filling potholes isn’t protected, cleaning road signs not protected, repainting markings, not protected. Libraries are not protected. We need money to ensure we can provide 20% of services unprotected by statute.”

There are two fronts when it comes to fighting coronavirus – one for national government, the other local councils.

But council leaders are worried that they don’t have the same megaphone or the same representation round the cabinet table, as, say, the Department of Health, which the Treasury confirmed on Sunday would get £3bn more in the spending review.

Mr Sunak was once a local government minister, but budgets are tight, and the reason Mr Osborne was able to squeeze local authority budgets was because it came with no political cost to the Tories in Westminster. So the dilemma continues.

For ministers, local councils are often seen as a cost centre. For voters, an everyday lifeline. Will the pandemic mean warnings are heeded this time?