Rishi Sunak set the tone for the spending review with his opening sentence: “Our economic emergency has only just begun”.

It sounded admirably frank. No chancellor in peacetime has faced such a sea of red ink, and even Mr Sunak’s slim-fit slickness couldn’t obscure the hole the UK is in.

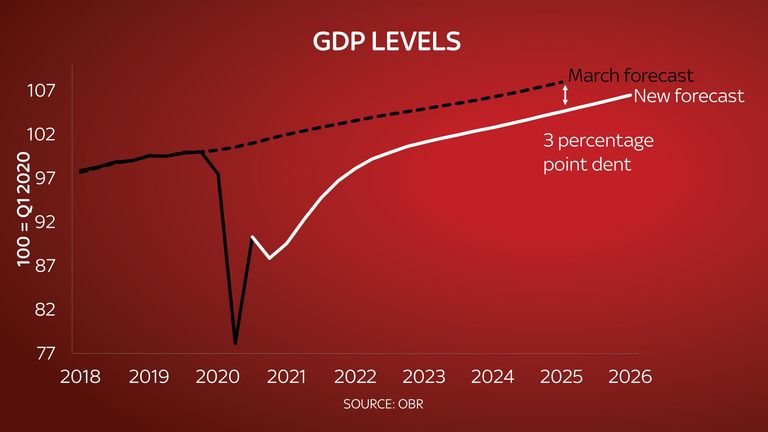

The economy will have shrunk by 11.3% by the end of the year, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR’s) central forecast, and will not recover to pre-COVID levels until the second half of 2022.

By 2025 GDP will still be 3% smaller than forecast at the time of the March Budget.

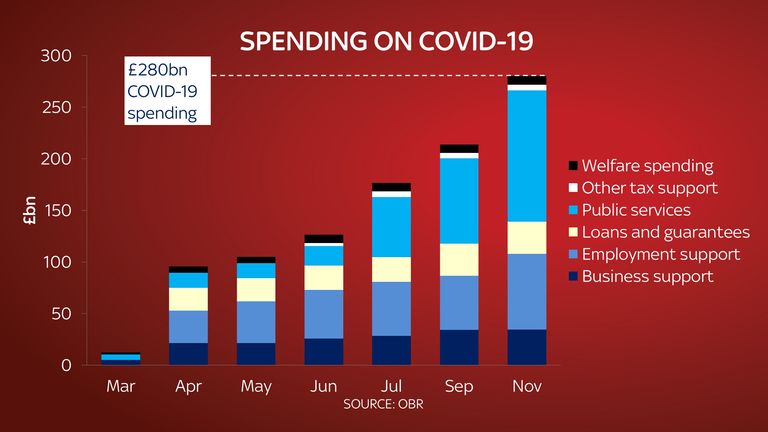

Borrowing to fund the pandemic response has been stratospheric; £394bn this year and another £164bn next, some £55bn of which will be for COVID-specific projects including NHS Test & Trace.

And unemployment, the devastating human metric of any recession, is forecast to reach 2.6 million people next year.

But this is only part of the story. Remarkably, it could soon be worse, and equally remarkably, the chancellor chose not to mention why.

The elephant in the room is of course Brexit, but Mr Sunak’s statement made not a single mention of the B-word, or even an acknowledgement of the cliff-edge that looms in just 36 days.

Fortunately the Office for Budget Responsibility, on whose forecasts the Chancellor relies, was not so squeamish, and its report sets out just how big a blow no-deal would deal an already reeling economy.

Overall no-deal would see a further 2% cut to GDP next year, delaying a return to pre-COVID economic activity by almost a full year, pushing recovery back from 2022 to 2023, and borrowing will increase by £10bn.

No-deal would also push up unemployment by 0.9%, equivalent to 250,000 more people losing their jobs and tariffs would increase consumer prices by 1% immediately.

More workers would be put on the furlough scheme and more government-backed business loans would default.

What free-trade deals the government is able to strike, such as those with Japan and Canada, would be “modest” and “unlikely to compensate” for failure to secure a deal with the UK’s nearest and largest trading bloc.

By 2025 the economy would still be 1.5% smaller.

The OBR says agreement on a free-trade deal would reduce the price the UK pays for the prize of sovereignty the Prime Minister has prioritised in negotiations. But even that best case will lead to a 4% reduction in GDP in the long term.

Of all this there was not a word.

The chancellor did set out a series of commitments he said would deliver a real-terms increase in departmental spending.

Health, defence, schools and criminal justice will all see increases, and there will be schemes to help the unemployed back into work, as well as a £4bn “levelling-up fund” for roads, rail and the like.

As to who will pay for all this, Mr Sunak offered only two candidates: key workers and the foreign poor.

A pay freeze will be imposed on public sector workers, with the exception of one million NHS staff and 2.1 million people earning less than £24,000, who will receive a £250 one-off rise.

That still leaves around two million people facing a real-terms pay cut.

The second cut was to the foreign aid budget, set in legislation at 0.7% of GDP but now to be trimmed to 0.5% until “fiscal conditions allow”, saving £5bn.

The parochial political benefits of this cut may be more valuable to Mr Sunak than the return to the taxpayer, though opinion is not uniform even on the Conservative benches.

As the man required to balance the books and a potential future Conservative leader he will hope the same applies to Brexit, whatever deal is struck.