“I knew he was a little bit out of the ordinary, a little bit weird.”

Lorenzo Rosa, unlike his father Georgio, says he never had ambitions to create his own micronation. In fact, he’s admits it was “a crazy thing to do… but those years were kind of crazy years”.

Bolognese engineer Georgio Rosa founded his own independent state – Rose Island – on 1 May 1968.

It was a 400-square-meter platform built from concrete, wood and steel just over seven miles (11.6 km) off the Rimini coast, amid the waves of the Adriatic Sea.

The island had its own language, coat of arms, currency, and most importantly – at 550 metres outside territorial waters – it was a free jurisdiction, separate from Italy.

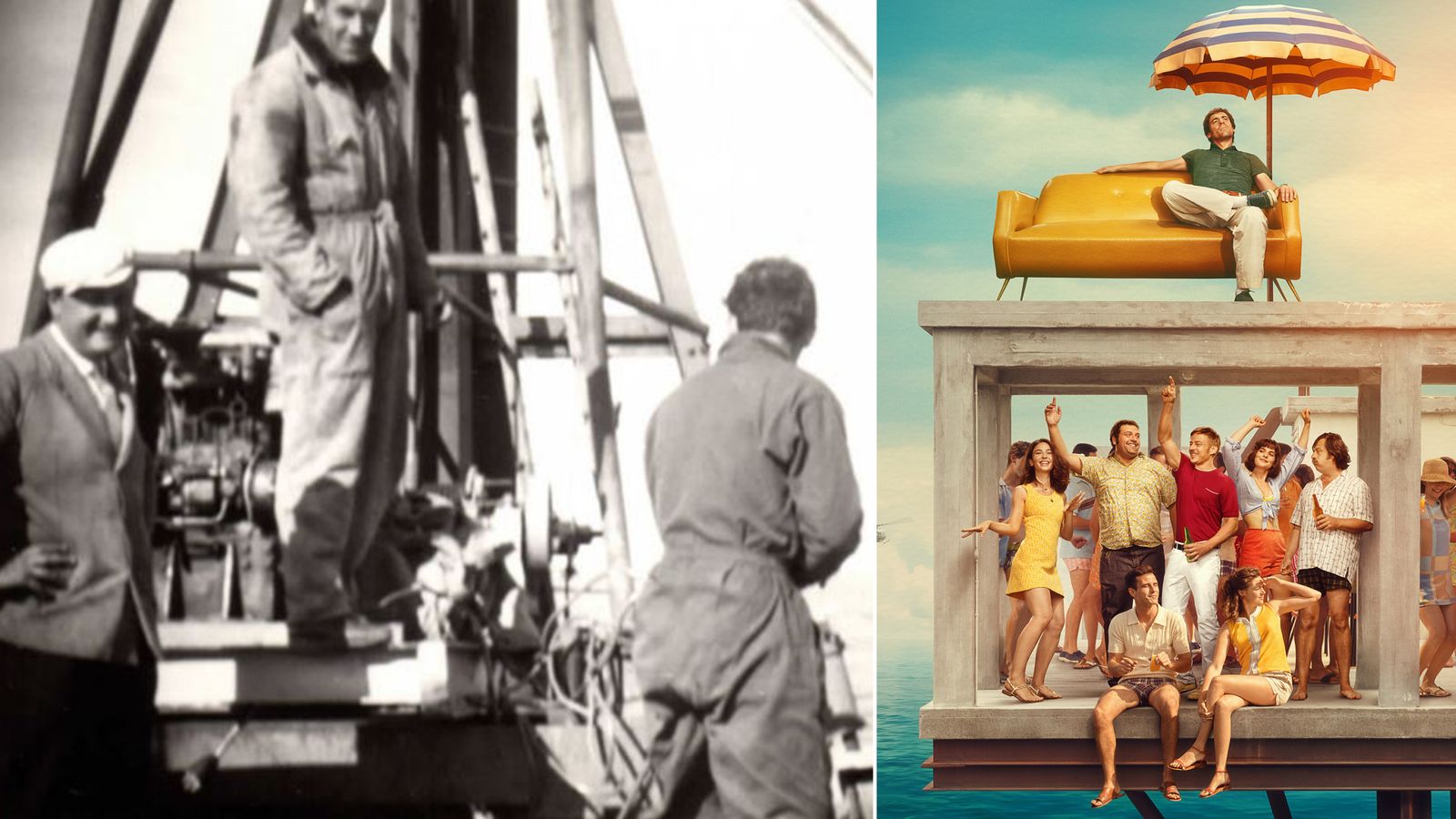

The stranger-than-fiction story is now being re-told by Netflix, in a two-hour film which the producer Matteo Rovere, describes as “85 percent true and 15 percent invention”.

While all the characters are based on real people and all the key events are accurate, some names have been changed to protect identities.

At a time when rules and regulations have become more important in our lives than ever – often at the cost of personal freedoms – it feels timely to look back at a man who struck out alone, determined to escape the system.

Talking to Sky News from Italy, Rovere explains: “[Georgio] dreamt of being the king of this whole world with no rules, with law that he can decide… It was a scream for freedom.”

Actor Elio Germano, who plays Georgio in the film, elaborates: “It was a period where people were dreaming. Everyone had their own idea about the future. At the moment it’s hard to imagine the future, so just to dream, is something.”

Taking place against the international backdrop of the Vietnam War and US civil rights protests, and sick of the stuffy rules of Italian society of the late 1960s, Georgio saw it as a natural progression to create his own nation, naturally appointing himself president.

Georgio’s son, Lorenzo, admits his childhood growing up with the engineering maverick wasn’t always easy: “When I told my friends that my father was building an island and maybe during summer I would go and spend time there, they would look at me as if I were a Martian, a person from Mars.”

He says he was accordingly tight-lipped over his father’s unusual exploits.

However, schoolboys aside, Georgio’s island soon attracted many fans – including a shipwreckee, Pietro Bernardini, who found himself seeking sanctuary on the island and went on to rent it for a year.

And once water was sourced (a freshwater aquifer was drilled 280 meters below the platform) the island was opened to the public, becoming a popular tourist attraction with visitors flocking from the Rimini coast.

The film’s director, Sydney Sibilia, tells Sky News that when he first met Rosa – who was by then 92-years-old – in his hometown of Bologna his first question was: “Why did you do that [build an island]?”

He says the answer was: “Why not?”. Sibilia admits, it was the perfect starting point for a movie.

Sadly, the team only met with Georgio twice, before his death in 2017.

The production drew on the engineer’s anecdotes, newspaper clippings, photographs and recordings of the time to put together the little-known story.

The technical details behind the build were also key to understanding the creation of the nation. It was apparently all down to “very good pipes”.

Lorenzo explains: “It was a modular system, he used these pipes – kind of like stilts – which were empty inside and then they would inject concrete in which made it very stable and very strong to hold the island.”

He says his father patented the hidden structures used to build the platform as it was “a much cheaper way of the building this system than the oil rig”.

It was only when recreating the island for the film (albeit in an infinity pool in Malta rather than the open sea), that the crew discovered first hand how tricky a feat it was to pull off.

Rovere says: “Because [Georgio] didn’t have much money, he used a very small crew of friends and some workers to build the island.

“When we built the island for the movie we spent a lot of money and we needed hundreds of people. It was crazy that he made the same with just some friends. He was a genius.”

However, despite its clever building techniques and stand-alone status, the island’s lifetime was not destined to be a long one.

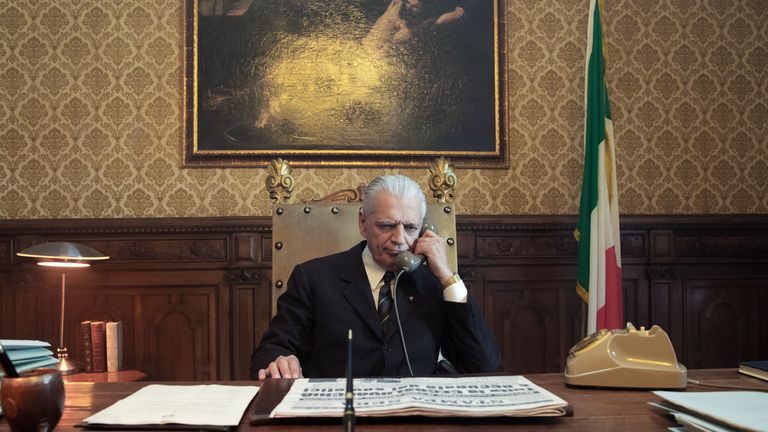

Just 55 days after its declaration of independence, the Italian navy cleared the island and set up a blockade to stop people re-entering.

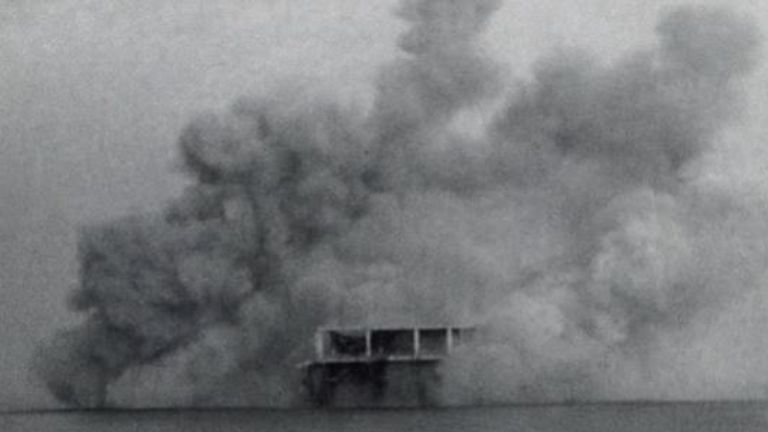

The following February, after government orders, divers placed explosives on the supporting pillars and attempted to blow it up with TNT.

Rovere says: “[The Italian government] tried to disassemble the island, but it was impossible, so they needed to bomb it.

“In reality, they needed two very hard bombings of the island to destroy it. And after that, the government sent [Georgio] the bill for the war… We saw the receipt.”

It turns out that even two bombings weren’t enough to dismantle Georgio’s work.

An act of god – in the form of a storm – finally delivered the coup de grace, destroying the platform on 26 February 1968. Today, its remains rest on the seabed.

It was a hard blow to its creator, his son Lorenzo explains: “Immediately after 1969, once the island had been destroyed, we couldn’t talk about the Island of Roses because it was a huge pain for my father and for the rest of the family.”

Sibilia agrees: “When I spoke with Georgio, I could tell it was no joke to him, it was a big deal. And that’s why this story deserves a movie.”

After dicing with the maverick engineer, the authorities made swift moves to prevent any possible recurrence, with the UN moving the boundary of the territorial waters from six to 11 nautical miles.

The destruction of Rose Island was the first, and only, war of aggression of the Italian Republic.

Rovere says: “After World War II, Italy never attacked any country, except this island, this dream.”

Subscribe to the Backstage podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

He says the effect of the destruction of the island had a bittersweet effect on its creator: “[Georgio] was resilient, and he was satisfied by the experience because he wanted to demonstrate the importance of individual freedom.

“He was obsessed by the fact that the United Nations should recognise that it was a real state. With the bombing Italy admitted it was another state, so from his point of view, it was a good result.

“He lost apparently, but in the deeper meaning in fact, he won.”

Rose Island (L’Isola delle Rose) starring Elio Germano and Matilda de Angelis is streaming now on Netflix.