Amidst the turmoil and rancour in Brussels, there is one sure thing today – the name of AstraZeneca will be in the headlines again.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) is due to give its statement on the safety of the company’s vaccine on Thursday afternoon.

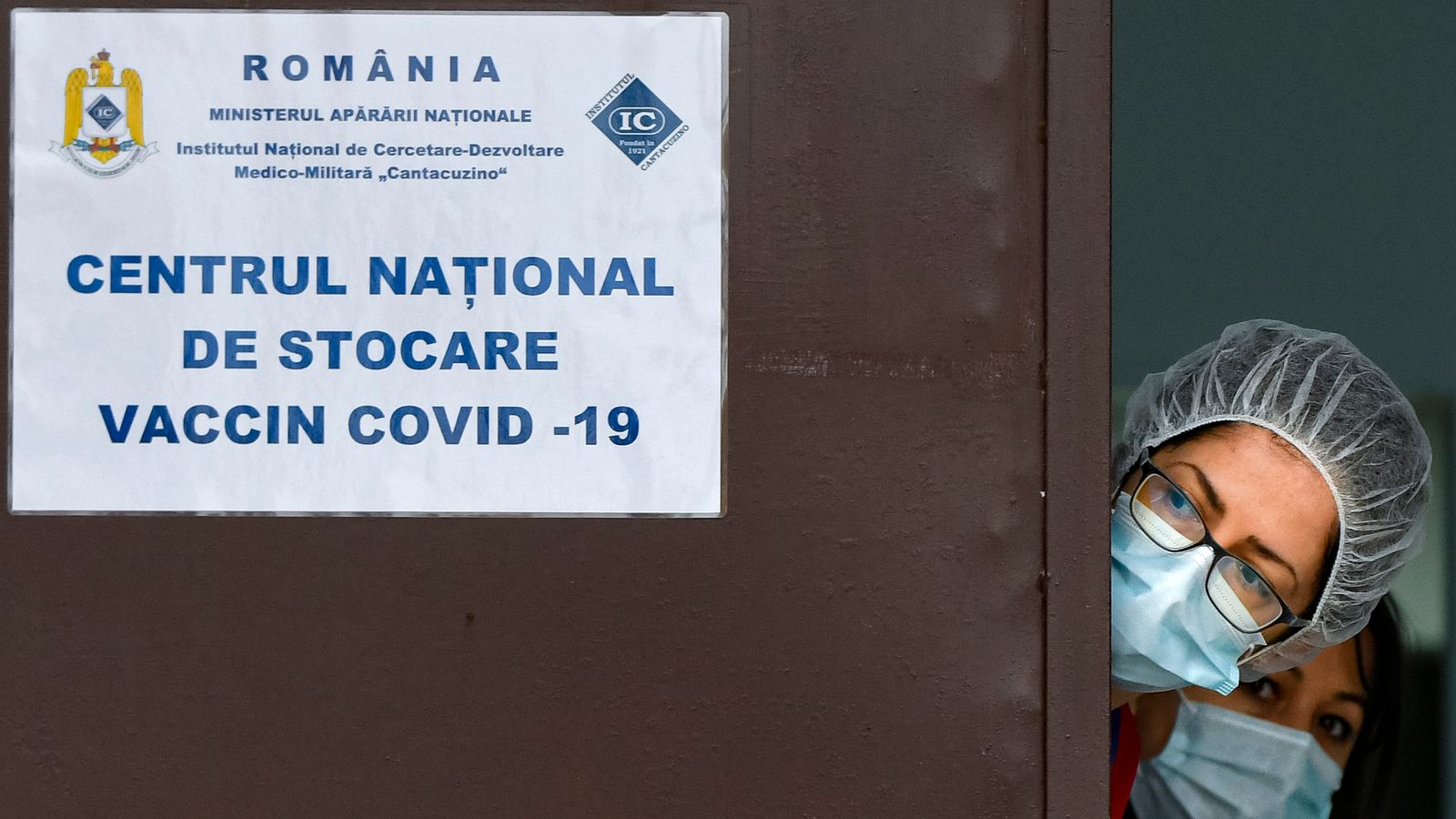

Most countries in the European Union have paused their use of the vaccine after asking for a review into a small number of cases where people have developed blood clots after being vaccinated.

The likelihood is that the agency will offer its reassurance that the AstraZeneca product is safe to use, and that the danger of any potential side-effects is far, far outweighed by the benefits that the vaccine can give an individual.

That is the position that has been stated by just about every prominent figure in the British medical community over the past few days.

Germany, by contrast, said it could not risk exposing citizens to unexplained dangers in a state-sponsored campaign, and that to do so would be immoral.

Neither side has seemed to relent in their conviction, although both agree that a swift, decisive and clear response from the EMA would be the best outcome.

That decision would bring some official closure, and it’s likely that vaccination programmes would restart almost immediately.

Despite accusations that the EU’s actions, in querying the safety of the vaccine, were politically motivated, this seems unlikely.

Most European leaders are far more worried about accusations of being too ponderous with their vaccine rollout than they are about some row with an international pharmaceutical company.

What they need, in order to save reputations and rebuild the confidence of voters, is a faster, more efficient vaccination programme. And that is where AstraZeneca’s second headache comes in.

The company’s relationship with the EU has been fractious, at best, over the past few months, marred by arguments over why it was failing to supply Europe with the number of doses that had been ordered. Tensions have simmered.

Now, that acrimony has boiled over. Ursula von der Leyen, the President of the European Commission, castigated the company for not providing enough vaccine doses.

What particularly irks Brussels diplomats is that the UK has, by contrast, consistently received exactly the supply that it ordered.

The British response to that is to point out that it not only backed the development of the vaccine, but also ordered it first, so deserves to get preferential treatment.

The EU retorts by pointing out that about ten million vaccine doses that were manufactured in European countries have been exported to the UK, while absolutely none have come in the opposite direction.

And now Mrs von der Leyen has raised the spectre of banning the export of vaccines.

She didn’t mention any target specifically but it’s clear that she was thinking of the UK when she said that the bloc was considering “all options”, adding: “If the situation does not change, we will have to reflect on how to make exports to vaccine-producing countries dependent on their level of openness.”

The threat is clear – either you start sending vaccines over to us, or we might stop sending vaccines over to you.

And the pressure is on. Across Europe, infection rates are beginning to rise again, sometimes sharply.

New restrictions have been introduced in Poland while, in France, Prime Minister Jean Castex is expected to announce new curbs, potentially including the return to some form of lockdown in Paris.

In Germany, Italy and beyond, politicians are having to face the prospect of tightening restrictions, rather than the easing they had hoped for. Everyone agrees that vaccinating populations is the only solution; the argument is how to get there.