It’s a familiar sight at Nigambodh Ghat, Delhi’s largest Hindu crematorium. A section of it carved out just for COVID-19-related deaths.

Hurried last rites performed on a 65-year-old man who succumbed to the virus this morning.

His loved ones have to bid a distant and hurried farewell – everyone deprived of a traditional ritual.

Sunita tells Sky News: “He died so soon, one of the biggest hospitals with all its modern equipment could not save him. My brother should not have died. This disease has torn our family.”

The virus has so far consumed close to 35,000 lives across the country. With over 1.5 million cases, India is the third worst-affected country after the US and Brazil.

Over the last few days, almost 50,000 positive cases are registered daily.

The government is always keen to point out the fatality rate of 2.23% is one of the lowest in the world.

That may be true, but coronavirus-related deaths are slowly but surely increasing, with no signs of it letting up.

In India, the state of Maharashtra with its capital Mumbai has been the epicentre of the virus.

It has had more than 400,000 positive COVID-19 cases, causing 14,165 deaths – three times more than the whole of China.

Dharavi, one of Asia’s biggest slums, had been the epicentre of the virus.

With more than 700,000 people living in 2.5 square kilometres, it is one of the most densely populated habitats in the world.

The slum has now made a turn around for the better but still remains a great concern for the government.

Earlier this month, World Health Organisation Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus praised the successful efforts at containment of the pandemic.

He said: “Even in Dharavi – a densely packed area in the mega city of Mumbai – a strong focus on community engagement and the basics of testing, tracing, isolating and treating all those that are sick is key to breaking the chains of transmission and suppressing the virus.”

According to a survey jointly conducted by Mumbai’s municipality and the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, about 57% of slum-dwellers have tested positive for antibodies for the coronavirus.

This suggests the metropolis could be heading towards herd immunity.

Dr Kamakshi Bhate, professor emeritus of community medicine at Mumbai’s King Edward Memorial Hospital, said: “Sero-conversion (the presence of antibodies in the blood) means you have protective antibodies.

“These are the people who are becoming a wall and protecting others against transmission.”

More than half of Mumbai’s population live in slums, their homes small and airless and making it easy for the contagion.

Social distancing, personal protection and hygienic living conditions are a privilege most cannot afford.

With this state accounting for almost a third of the country’s death toll, its hospitals have been overwhelmed.

Bada Qabristan, a Muslim organisation, are lending a helping hand. Putting themselves at risk, they are conducting last rites for abandoned bodies and for those families too scared to conduct rituals.

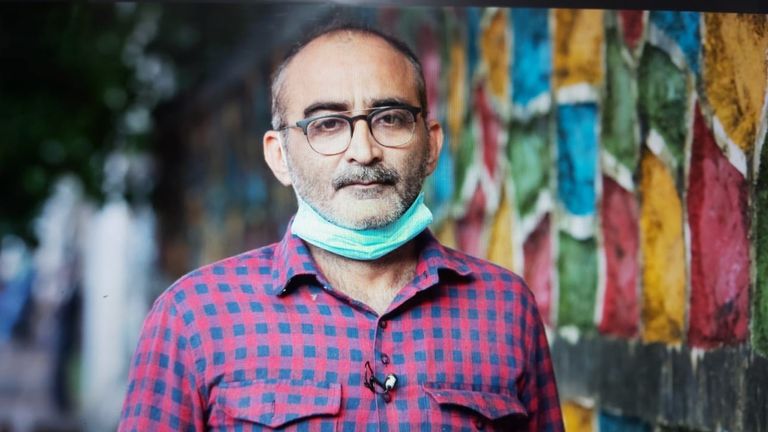

Iqbal Madani, a member, told Sky News: “While we looked for Muslim bodies in mortuaries we found unclaimed bodies of our non-Muslim brothers and sisters.

“Families just too scared, some were in quarantine and unable while some so fearful they will contract the virus if they touched the bodies – so they stopped claiming them.”

What started out as a 20-member team has grown ten-fold.

They come from all walks of life and spend their own money and time to pick up bodies from dozens of mortuaries across the city. They have performed last rites for more than 800 bodies in Mumbai.

“Be it of any religion, we want to give the person some dignity in death, we want nothing but prayers,” said Iqbal.

:: Listen to the Daily podcast on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, Spreaker

Speaking at a virtual programme to mark the opening of COVID-19 testing facilities, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said: “India is in a much better position than other countries in the fight against the pandemic due to the right decisions taken at the right time.

“The world is praising us because of the efforts of the foot soldiers. Our country has come to a point where it does not lack in awareness.”

The Indian government spends just over 1.2% of its GDP on public health care. This has been going on for decades under successive governments, resulting in inadequate health care for the masses.

More than 70% of Indians go to private care, as public health infrastructure is creaking and in many places non-existent.

At the main district hospital of Chapra in Bihar, one of the poorest states has telling signs of government apathy.

Ward after ward is bereft of basic medical equipment, though filth and squalor can be found in abundance.

Betel nut spittle lines the walls, doors and corners of the hospital. Used syringes, medical tubes and empty bottles are strewn all around.

There are no signs of doctors or any nursing staff as patients are left on their own.

Rupesh Kumar came in with breathing problems and was attached to a device which would help him breathe easier – but that doesn’t work. He’s been waiting a while for assistance.

“It’s just too dirty here, no bed sheet either, I can get more sick here,” he tells Sky News.

The hospital has a coronavirus isolation ward attached to it.

Used PPE and bio-medical waste lie discarded in the open at one end of the hospital grounds. Pigs roam the hospital complex scavenging on it.

The pandemic has also breached the rural parts of the country, with positive cases reported in small towns and villages.

Migrants affected by months of severe lockdown have returned and could have inadvertently carried the virus to all corners of the country – a big concern for the government.

India’s struggling public health structure would be no match for a severe pandemic and would collapse, ravaging its people.