Some British ports will find it “impossible” to carry out checks on fresh food and plant imports in the event of a no-deal Brexit, industry groups have warned parliament.

Ports around the UK face fundamental changes to customs arrangements in just 45 days’ time when the EU transition period ends on January 1.

Deal or no deal, they will be required to implement sweeping changes to border checks after more than 40 years of European Union membership.

The impact will be more dramatic however if UK and EU negotiators, meeting in Brussels this week, are unable to reach a deal, with potentially disastrous consequences for smaller ports.

Appearing before the House of Lords EU goods sub-committee, the British Ports Association (BPA) said some will not be able to cope if customs consider all EU produce in the way that non-EU “third country” imports are currently treated.

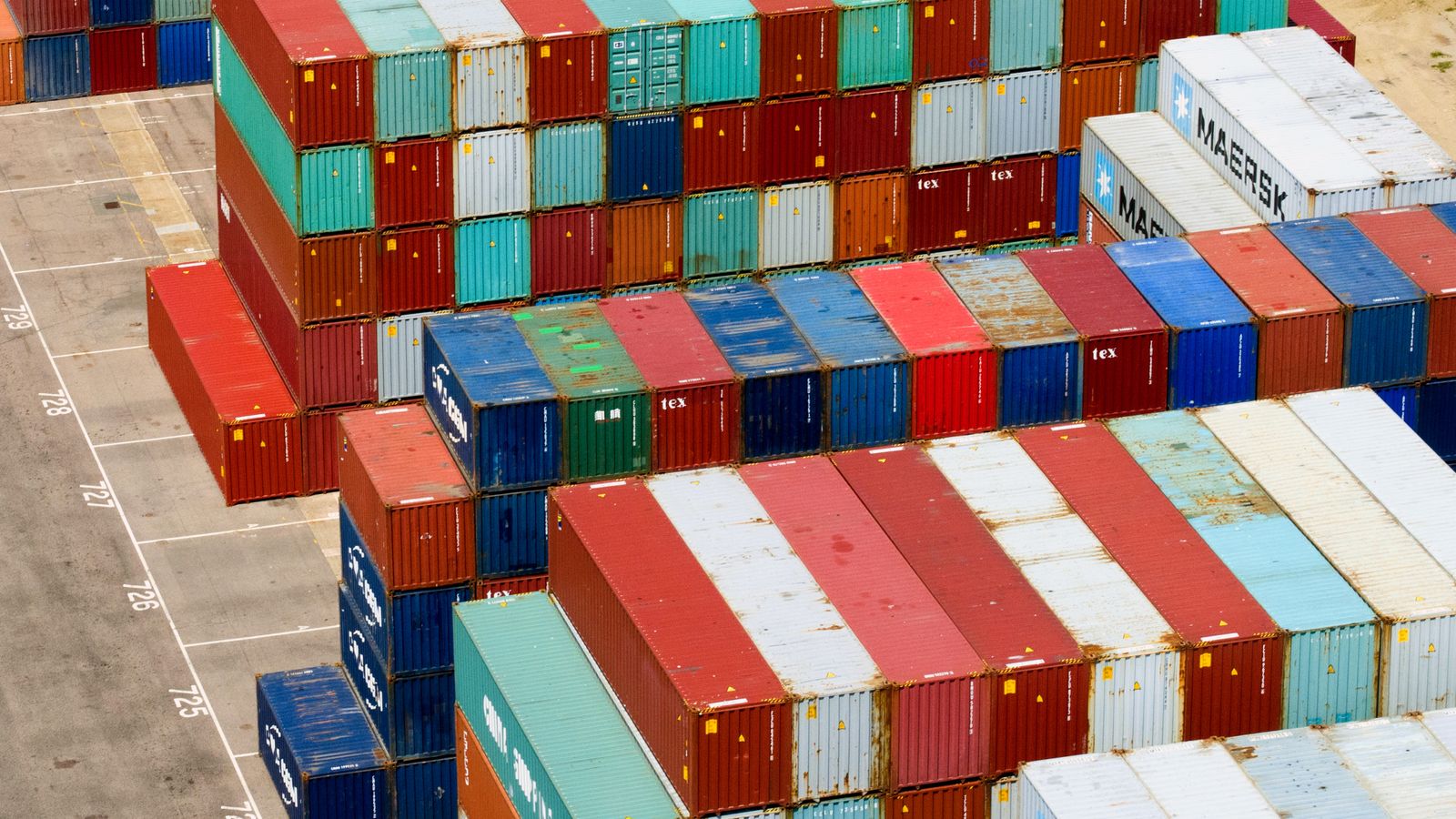

The warning comes as Britain’s largest container port at Felixstowe was described as being “in chaos”, with shipments delayed and several ships being diverted elsewhere.

Port operators also raised concerns that a key piece of government software for hauliers, intended to enable smooth border processes, will not be launched until a fortnight before Brexit day, and complained that getting information out of government had been “agonising”.

“The things we have needed to know about, it has been agonising getting information out of government,” Richard Ballantyne, chief executive of the BPA told peers.

“The Animal and Plant Health Agency effectively set specifications about the amounts of checks goods coming in from outside the EU should be subject to.

“Their regimes that mirror those third-country checks in a no-deal situation, as we may find ourselves in, effectively could be completely impossible for certain ports to accommodate with any practical, sensible approach.

“It would put traders at a real disadvantage bringing their goods on certain routes if they know that a high percentage of those volumes need to be opened and inspected. We have found that very challenging.

“Remember a lot of our goods come in from places like Rotterdam, our salads and other fresh foods and meats.

“To stop those and inspect and open those consignments is something we really need to think about.

“This is all a consequence of our de-listing from the single market, effectively our goods are subject to the full frontier controls.”

The government has offered two solutions to the requirement to carry out huge volumes of new documentary and physical checks on imports.

One is for ports to carry out checks on site, something many have no space to do.

The other is for goods to be transported direct to lorry parks that will be used as customs clearance centres, including a new facility at Sevington, near Ashford in Kent.

The second model relies on traders and hauliers to use a new software system, the Goods Vehicle Movement System, which is still in development and will not be launched until two weeks before the transition period ends.

Also questioned by the committee was Mark Dijk, external affairs manager at Rotterdam, the largest container port in the world.

Asked how it had been able to make preparations earlier than some of its UK counterparts, Mr Dijk said: “We have always said that whatever Brexit it is will be a hard Brexit.”