British and EU negotiators will return to the negotiating table today in a “final throw of the dice” as they try to secure a post-Brexit trade deal.

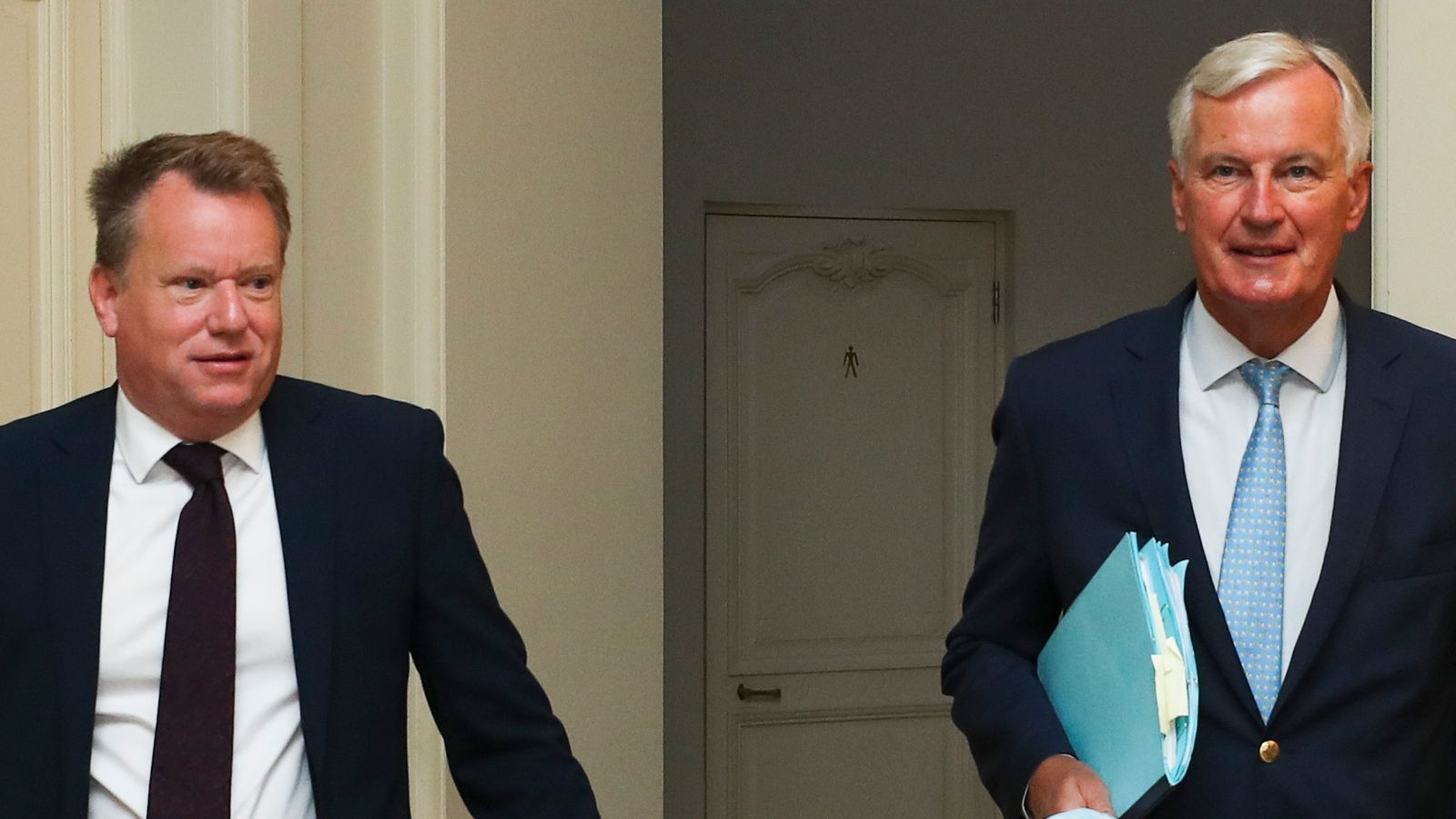

With time running out before the Brexit transition period ends at the end of the month, Britain’s chief negotiator Lord Frost will reconvene talks with his EU counterpart Michel Barnier in Brussels to try to resolve “significant differences”.

But British sources have warned that the process may still conclude without an agreement.

“This is the final throw of the dice,” said one source close to the talks.

“There is a fair deal to be done that works for both sides, but this will only happen if the EU is willing to respect the fundamental principles of sovereignty and control.”

Today’s meeting follows an hour-long call on Saturday between Prime Minister Boris Johnson and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, in which they agreed on a final push to get an agreement.

In a joint statement following their discussion, Mr Johnson and Ms von der Leyen said that while “progress has been achieved in many areas… significant differences remain on three critical issues: level playing field, governance and fisheries”.

The level playing field refers to state subsidies and standards: the EU fears that Britain could become a low-regulation economic rival, cutting standards and heavily subsidising its industries.

In the statement, Mr Johnson and Ms von der Leyen said: “Both sides underlined that no agreement is feasible if these issues are not resolved.

“Whilst recognising the seriousness of these differences, we agreed that a further effort should be undertaken by our negotiating teams to assess whether they can be resolved.

“We are therefore instructing our chief negotiators to reconvene tomorrow in Brussels.

“We will speak again on Monday evening.”

The negotiations on a potential trade deal between the UK and EU have gone down to the wire, with time for an agreement rapidly running out.

It comes after a week of intense negotiations in London, with late night sessions fuelled by deliveries of sandwiches and pizza.

Britain wants to “take back control” from Brussels and set its own economic policies.

The fishing industry is another obstacle – a small part of the European economy at large, but very important to nations such as France.

The EU wants to continue to fish in British waters, but the UK wants to control access and quotas.

What is unclear from the joint statement from Mr Johnson and Ms von der Leyen is whether either – or both – of the two leaders was prepared to shift ground during the call in a way that would enable their negotiators to bridge the gaps.

In the run up to the call, the UK accused the EU side of seeking to introduce “new elements” into the negotiations at the 11th hour.

The British side was angered by reported demands by Brussels that EU fishermen should continue to enjoy the same access to UK waters for another 10 years.

There was concern that Mr Barnier was coming under pressure from French President Emmanuel Macron at the head of a group of countries which feared he was giving too much ground to the UK.

Ireland’s Prime Minister Micheal Martin said he welcomed news that negotiators would resume their discussions in Brussels on Sunday.

“An agreement is in everyone’s best interests,” he tweeted. “Every effort should be made to reach a deal.”

Analysis: A deal remains favourite – but it’s not certain

By Adam Parsons, Sky News Europe correspondent

On the face of it, this is like putting a cup more petrol in an empty fuel tank. The car might trundle on for a mile or two, but it won’t get you home.

Brexit talks have been stuck for months now over the familiar themes of fishing, governance and competition rules, known as the level playing field.

For day after day, negotiators have wrestled with how to find an agreement – and have consistently failed. So how will a few more days help?

If it was just down to the pressure of time, that would have worked by now.

What’s required now is for new instructions from above – and in the case of the EU, that means giving more wriggle room to chief negotiator Michel Barnier.

The problem is that some countries – including France, the Netherlands and Belgium – have already complained that they think he’s giving away too much to the UK. Would they really be happy to let him make further concessions?

The same challenge faces Boris Johnson and Lord Frost (the UK’s chief Brexit negotiator) – how to strike a deal that looks sufficiently hard-won to satisfy Brexiteers, but is also palatable to the EU.

It will take compromise, and at pace. Proper diplomatic high-wire stuff and, among senior sources I speak to, there is no consensus about what will happen.

Most still expect a deal, but perhaps because that’s how negotiations often work – crisis, anger, broken deadlines and then agreement at the last minute. The choreography, they insist, is part of the process.

But there has never been a deal quite like this one.

On Monday, the Internal Market Bill, which is utterly hated by the EU, is back in the House of Commons.

The European Council meets on Thursday. And the French have already said they would be prepared to veto a Brexit deal if they hate it.

The truth is that, right now, nobody knows what’s going to happen. A deal remains favourite, perhaps because no-deal is seen as so economically damaging. But it’s not certain.